The Hard Times are upon us, in a twenty-first century iteration. The staggering incompetence of our institutions is bleak, and the idealized lifestyles put forth by the celebrity elite are boring. Somewhere between buying hyper-saturated boxes of retinol to look twelve until you die (overconsumption), “focusing on yourself” to “protect your peace”(isolation), and disillusioned exhaustion (numbness), I’ve found our modern answers for cope discouraging. I’ve had the privilege of attending some lectures in the past few weeks that have illuminated a way of reimagining the world, so that we may find a new way of living in it. Here is what I have to say about it:

Part I - The Good Society

The Gilded Age

I love history. I know this because I send embarrassing things about getting “chills” to my friends in the middle of lecture.

Because I love history, I find myself cautious of the oversimplifications embedded in the whole “history repeats itself” ordeal. Historical narratives are typically fashioned to the ways we view the world now, with history itself being a dynamic, living practice. That being said, some eras are objectively more similar than others. That being said, at least once a week in my Gilded Age lecture Professor Fronczak throws his hands in the air, saying “you can’t make this up”, shaking his head in disbelief.

I don’t think you need a whole course on the Gilded Age (though I’ve enjoyed it immensely) to know it was also Hard(er) Times. Between the extreme economic exploitation, voter suppression, and “captains of industry” who shaped policy for their financial gain at the detriment of public interest, the world for the majority of people in America looked bleak. Enter Edward Bellamy, and the Golden Age of Utopian Dreams.1

A brief history of utopian writing

In 1516, Sir Thomas More published the seminal Utopia. Utopia translates literally from Ancient Greek to “no place”, and centers on the social structure of a fictional New World commonwealth state. While Plato’s Republic had broached the nature of justice and virtue in the ideal society, More was the first to reimagine the concrete details of political and social organization as a means to happiness. When Edward Bellamy published Looking Backward: 2000-1887, he was following in the footsteps of More’s imagined construction of the Good Society.

In Looking Backward, Boston aristocrat Julian West falls into a hypnotic sleep in 1887 and awakes in the year 2000 to a transformed socialist utopian society. Bellamy uses this narrative device as a means of critiquing the economic and social conditions of the Gilded Age, proposing a radical reimagination of American society. It was a rapidly popular hit, selling over a million copies across multiple languages.

Looking Backward is, honestly, not that good of a novel. I found the writing clinical and the characters flat. It turns out a utopian society is not a primed setting for the tension that drives compelling literature. Still, middle class citizens of the Gilded Age responded to the hardship of the era by using utopian writing as not only a means of escapism but a way to critique and reimagine American society. They even went as far as to create Bellamy Clubs, which held weekly meetings to idealize the utopian world and discuss the means of social transformation to achieve it. Utopian storytelling eventually lost its popularity early into the twentieth century, as the prosperity and disposable income of the roaring twenties dispelled the urge to write about the idealized world. But in the late nineteenth century, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the hotspots of working class culture and utopian writing overlapped. The laboring class and its writers exercised utopia as a means of identifying what meant most to them, and from there decided what they could compromise on.

The takeaway

The Gilded Age was Hard, but it also gave way to something better. Not the socialist utopia of Bellamy, but social work and direct election of Senators and graduated income tax. The national parks and the conservation movement and the reformers. None of this was inevitable, but it was enacted by diverse, flawed people who believed in diverse, flawed institutions and dedicated their lives to the public process.

Trying to conceive of a utopia or, at the very least, the Way You Want to See Things Going, may not seem like a productive or radical act. But if you approach the future with a chronically cynical, pessimistic, and/or apathetic outlook, you essentially surrender all personal agency in your life. If you are not looking for solutions, you are stripping yourself of your power to create change.

The opposite of love is not hate but indifference. In the same vein, the opposite of utopia is not dystopia but the idea that utopia isn’t worth imagining. Writing a utopian world is an immensely difficult challenge because it is not easy to imagine the specific structures of a perfect city or nation, how it values work and lesiure and justice and art. But, like the working class thinkers of the Gilded Age, coalitions need compromises, and compromises need to be based on an identification of values and virtues. Imagining utopia is a place to start.

Things are never so terrible that it would be impossible to move an inch closer towards our ideals, to live up to our values. Workers of the Gilded Age faced routine, violent (and occasionally lethal) suppression over campaings for the 8-hour work day. And still, they read and wrote and demonstrated and dared to imagine a better world. I think we owe it to ourselves to do the same.

Part II - The Good Life

A Talk With a Monk

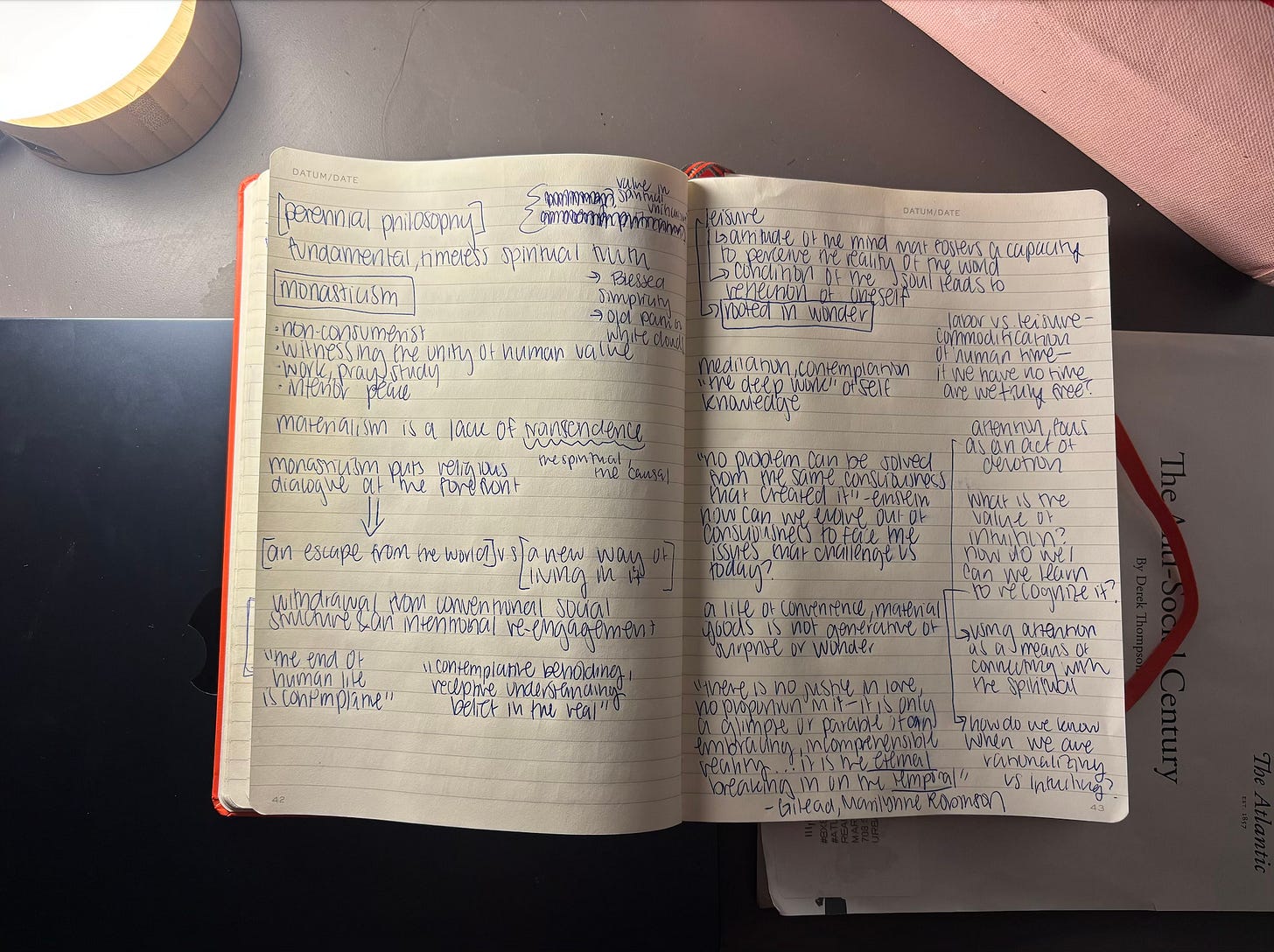

There is an Official Lecture Name for this that I am not privy to, because it was part of the University’s Last Lectures series for the outgoing seniors, surely stacked between weeks of Successful People in Finance. I am also going to admit that my notes on this aren’t nearly as comprehensive as the lecture itself, so I sincerely hope I am not misrepresenting the teachings of Cyprian Consiglio (one of the first things I learned about Camaldolese monks is that you get to pick a new name, which I find quite cool and think they should advertise more in their recruiting).

But I think this lecture was an important supplement to the utopian view of the Gilded Age. I realize that a lot of what I write about Society distills to “Go Outside, Talk to People, Know Your Values!!!” which can be repetitive and self righteous, but is certainly what we should all be doing more of. These directives are simple but not easy. The problems that lie in our institutions also lie in us. Algorithms are engineered for us to be pulled inside, on our own, in streams of content that distract us from tapping into our higher consciousness, or any consciousness for that matter.

The potential benefit of the Hard Times is that there is renewed importance of defining and living in accordance with your Values. Consider the Good Society but also consider the Good Life. Is the Good Life being marketed to us really the Good Life we want? Having a 24 karat gold encrusted Waygu steak or a billion Instagram followers or a new Miu Miu outfit every day for the rest of your life is not awesome. Literally, it will not bring about awe or wonder. It will not satiate your spirit. That is because at the heart of materialism is a lack of transcendence (Cyprian’s words, not mine, so if you think I’m being too preachy you can argue with the monk).

Of course none of this is new. I think I’m in pretty good company on the whole Hedonism is Unfulfilling front. But we have to keep coming back to the Same Ideas because the world changes and then we forget. Philosophy and religion must run as fast as they can just to stay in the same place.

Okay, so, how do we transcend??? If I knew the answer to this, I would probably not own 26 pairs of pants. Cyprian suggested this involves the “deep work of self knowledge”. Which is difficult, because it requires a sustained concentration of difficult tasks in an environment free of distraction. It requires mental effort. Then, even when you put in the effort, the output of things that spiritually challenge us (as opposed to things that are pleasurable) is less measurable and thus less recognizable to ourselves as Good. When you finish a ten minute meditation, you can’t objectively say you are X units More Spiritual than when you started. This does not compute well to our modern mind.

I still think meditation is useful, caveating that I’m not that good at it and don’t do it as often as I would like. We are so conditioned to tell “our story” to the world that only when we sit alone with our thoughts are we really challenged to be honest. No judgement. We spend so much time hiding the “deepest” parts of ourselves from the world that we begin to hide them from ourselves too. Building walls without really understanding what’s being guarded. Soothing the agitation of not knowing oneself with distractions, of which the present world readily provides. Meditation allows us to subvert this dynamic and begin seeking out the parts of ourselves we are most uncomfortable with.

Life is not a series of logical choices. Going through it by making the most logical choice at every turn is not a means of self realization. We are not machines!!! We are people!! So you do the deep labor, you gain a working knowledge of yourself. That is where we can refine our intuition and illuminate our values. Your intuition tells you when you’re learning something you love or meeting somebody who will be important to you. It will not tell you to purchase mindlessly or study something you hate because it will make you millions of dollars. Your intuition compels you to stand for something, to say I believe in God, or the government, or the good in other people. This is difficult because it takes the liability of being wrong, but I don’t think our most intuitive self is particularly risk averse. Sometimes, without reason, you just feel something. That, I believe, is the transcendent breaking into our temporal world. That is the wonder.

Joseph Fronczak, The Golden Age of Utopian Dreams, Lecture, History 377: The Gilded Age and Progressive-Era United States, 1877-1920, Princeton University, Spring 2025.